These passages have been referred to as "torture porn." Sadomasochistic they certainly are, but porn is entirely in the mind of the beholder. They begin to inflict pain on each other in unspeakable and shockingly intimate ways. He and She don't much seek refuge in their cabin but increasingly find themselves outside in the wilderness. The woods are inhabited by strange animals that look ordinary - a deer, a fox, a crow - but are possessed and unnatural. The psychic pain of his counseling and their removal to the forest are now joined by pain inflicted upon them by nature and each other.

They have already eaten of the fruit, and it will never be Eden for them again. The cabin is named Eden make of that what you will. This leads to pain, most directly when he insists, at this of all times, on their going to their remote cabin in a dark woods that she fears at the best of times.

Her grief is her fault, you see, and he will blame her for it. For reasons he may not be aware of, he is driven to deal with her guilt as a problem, lecturing her in calm, patient, detached psychobabble. Of course they blame themselves for having sex when they should have been attentive to the infant. Their error is in trying to treat it instead of accepting it and living it through. He is a controlling, dominant personality, who I believe is moved by the traumatic death to punish the woman who delivered his child into the world. She has been doing research on witchcraft, and it leads her to wonder if women are inherently evil. In any case, all the ideas of the film are so extravagantly and feverishly expressed that one fears that von Trier, always working on the edge, has finally become unhinged.We must begin by assuming that He and She are already at psychological tipping points. (“Nature is Satan’s church,” the wife utters apocalyptically at one point.) This focus on nature subsequently gets conflated with human nature and finally with female nature, where von Trier’s careerlong misogyny comes into fullest bloom. The film’s most successful thematic confrontation is that between frail reason (embodied in the pathetic, infantilizing attempt by the husband, who’s a psychotherapist, to treat his deeply disturbed wife with cognitive therapy) and the uncontrollable forces of emotion and mystery that emerge victorious.Īnother powerful idea, that nature is cruel and vicious and completely antithetical to human welfare, seems to align von Trier with the German visionary director Werner Herzog. Or horror, as when genitals are scissored off, masturbation produces blood rather than semen and holes are drilled into legs. Hence, many of von Trier’s more outrageous, ultra-serious symbolic moments (such as a talking fox, its guts half ripped out, muttering “chaos reigns” in an “Exorcist” voice) will - and did, in the press screening - undoubtedly provoke unintended laughter. Clearly, or rather not so clearly, von Trier is working in a full-out symbolic vein here, as did Strindberg late in his career, but alas, the film medium inevitably carries with it, like an albatross, a heavy charge of realism. In discussing this self-styled “most important film of my career,” von Trier has referred to the forbidding Swedish playwright August Strindberg. The fact that the first three are “Pain,” “Grief” and “Despair” does not bode well. At this point, von Trier switches to color and his signature chapter headings. Bereft, they retreat to Eden, their ironically named cabin in the woods, to recuperate from their loss.

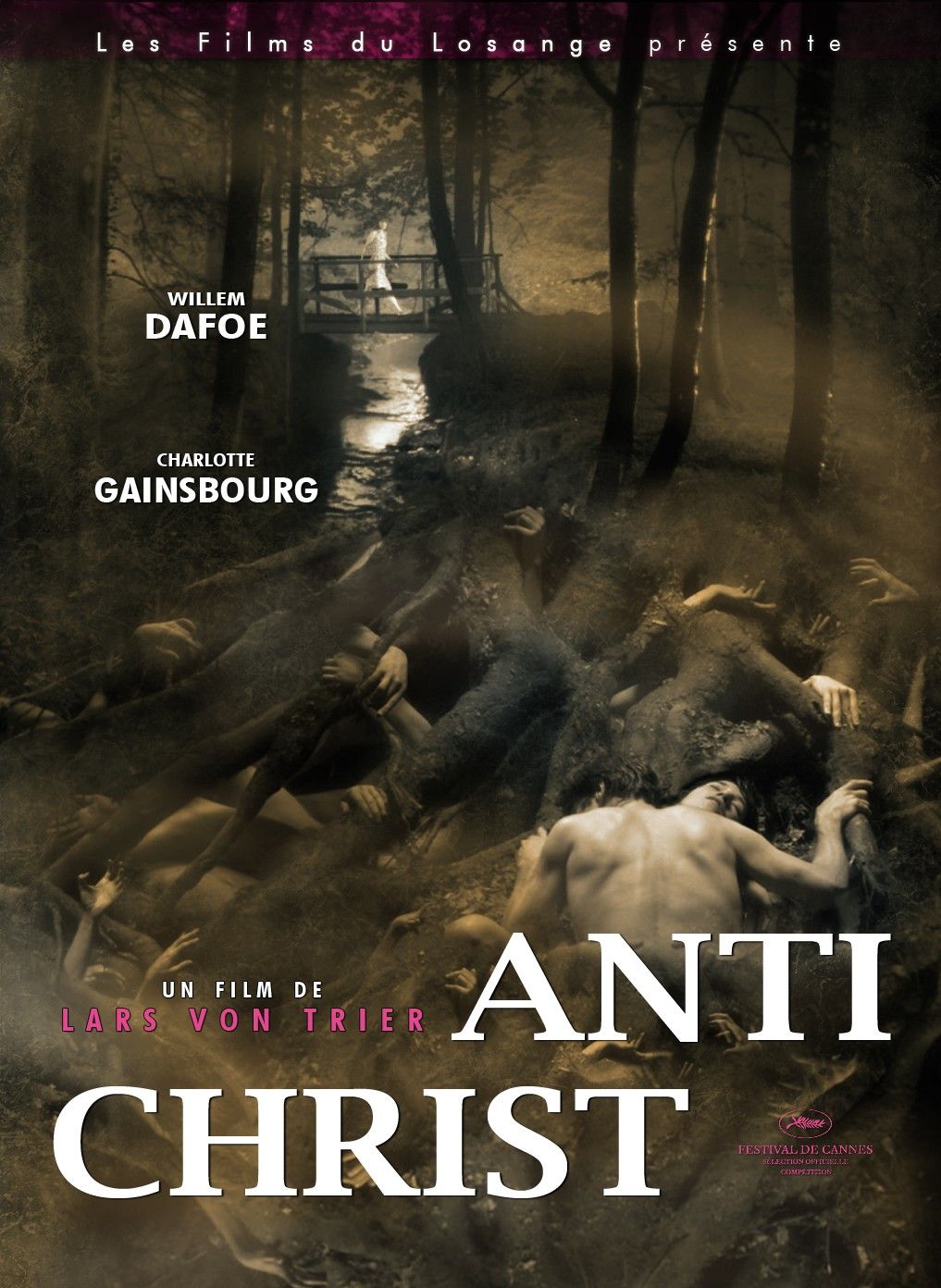

As we learn in a rather pretentious prologue shot in slow-motion and black and white, their toddler son has fallen to his death through an open window while they were making love. “Antichrist” is relentlessly and solely focused on a married couple, played by Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)